Licensing#

Fig. 34 Licensing. The Turing Way project illustration by Scriberia. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3332807.#

Prerequisites#

No previous knowledge is needed, this chapter explains how important it is to understand how laws and licensing can affect your project.

Summary#

This chapter was written using American English, in which the word license is a noun and a verb. With British English, however, licence is a noun (as in, to issue a licence), while license is a verb (as in, they licensed the event).

‘Intellectual Property (IP)’ law is a complex subject. However some understanding of it is important for anyone producing creative works governed by it including software, datasets, graphics and more. This is true irrespective of the nature of your project: Closed commercial projects building on open tooling; Commercial projects maintaining an open resource; Open community driven and/or non-profit projects. Each of these may need to make slightly different licensing choices from the beginning of their projects to be compatible with their goals.

This chapter aims to give a brief summary of relevant intellectual property laws (enough to be able to read most software, and related licenses), explain free and open source software licensing, and explain how combining software from different sources works from a legal perspective. Decisions about licencing made at the inception of a project can have long-lasting and significant ramifications. The choices that you make about how your work is licensed shape who can and cannot legally use your work and for what purpose. Consequently, this chapter will feature some discussion of the ethical ramifications of licensing choices. It aims to be informative about the implications of licencing choices for the use of your work but not to prescribe a specific ethic, as there are divergent schools of thought on the ethics of different licencing choices.

Many of the concepts which apply to the licensing of software, data, AI/ML models, hardware and other creative works such as visuals share common attributes and concepts which will be covered here. We will address the specifics of licensing each of these types of output in their own sub-chapters, as well as a separate sub-chapter on license compatibility.

Intellectual property is an umbrella term that refers to a number of distinct areas of law, primarily these three:

What these have in common is the attempt to extend property rights to intangible goods, meaning their use by others can be prevented or licensed. Governments with such laws effectively create a limited grant of monopoly over these goods for their creators, and other holders of these rights. This is generally done with the ostensible intent to incentivise the creation and improvement of such goods, but can in practice result in perverse incentives which fail to do so.

Warning

It is important to consider that copyright, licenses, and patents are all legal concepts. As such, they are subject to what the law prescribes, which may change over time and space. Simply put, different countries have different laws, and follow different procedures with regard to enforcing them. The content provided here is broadly based on American and European law and legal traditions. It might not be applicable - might even be contra indicated - or relevant in your particular context. However most nations are signatories to international treaty agreements which somewhat harmonise these laws notably the Berne Convention, the TRIPS Agreement, and others under the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Whilst international efforts have sought to harmonize copyright enforcement, the real world is a messy place.

Good legal advice is timely, specific, and given by an expert; this chapter is none of these. It was written by engineers & scientists, not by lawyers, and it is a heavily simplified overview of a very complex field. The intent is to give you an overview of the basics so that you will know when to check whether something you want to do has potential legal ramifications. Do not make any important decisions based solely on the contents of this chapter.

So do not take the descriptions provided or viewpoints shared as legal advice, they are not that. This document is not intended to be used in that manner. Consult a legal expert to provide actual legal advice for your case.

Perhaps the most relevant part of intellectual property law for software, data and other creative works is copyright. We will dispense quickly with patents and trademarks here, so we can move on to the main topic of copyright.

Patents#

The most important difference between patent and copyright to be immediately aware of is that by default all rights are retained by the author on works made public under copyright, whereas patents must be registered before their content is publicly disclosed. Thus, if you want to patent something, you must do so prior to sharing it publicly. The precise details of what constitutes a disclosure and the strictness of the application of this rule can vary by jurisdiction.

Patents on processes and software rather than specific inventions are a matter of contention in US law and explicitly not recognised in EU law (at time of writing). Unlike copyright, you generally have to pay to register and maintain a patent. You must also do so in each jurisdiction in which you want this patent to apply, though some have reciprocal agreements for recognising patents from other jurisdictions. To ensure that patents held by the authors of software do not impact on the freedom to use and distribute open software, some licenses specifically include permission to use any applicable patents (for example section 3 of the Apache 2.0 license), though this cannot protect against patents held by 3rd parties.

Trademarks#

Trademarks are a brand, symbol, or identifying mark associated with a project, product or service. Trademarks differ from the copyright & patent in that their primary function is consumer protection. They prevent bad actors from impersonating recognisable brands and deceiving consumers into purchasing products that are not being offered by who they think they are. They, like patents, must also be registered, but unlike patents, this can be done after they have been made public.

Registering a trademark generally comes with an administrative fee, but is not as costly as maintaining a patent. Trademarks generally only apply within a specific sector, as people are unlikely to confuse brands which do completely different things. They can be relevant in the context of the name and logo of a software project, especially when a project changes hands or is forked, in which case the fork may not be able to use the original name of the project even if that project is no longer maintained. Open source projects not associated with a company which have trademarks may have these held by a legal entity such as a non-profit, through which they might also take donations and pay for project infrastructure. It can be valuable for open source projects to register for trademarks as their work can easily be cloned, modified and re-distributed with ill intent. Examples of modified open source tools distributed with malware added have been documented, and trademark enforcement could in some cases help to prevent or deter this. Nextcloud, for example, has a very comprehensive guide to the use of their marks with excellent explanations for the restrictions that they place on their use.

Copyright#

By default, if you make a work publicly available, you retain the copyright to that work and all rights that this gives you over it. Anyone wishing to re-use that work must seek to license the right to do so from you, or open themselves to the possibility of a lawsuit for infringing on your copyright. Irrespective of how you choose to license your work, however, there are some generally accepted exceptions to the protections of copyright that permit the re-use of works (or parts of works) without the consent of the copyright holder, under certain circumstances. These are known as ‘fair use’ or ‘fair dealing’ exceptions. Under the ‘fair use’ standard originating in the USA, the following criteria are considered on a case-by-case basis to decide if a use constitutes an infringement of copyright:

From 17 U.S.C § 107

the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

the nature of the copyrighted work;

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The ‘fair dealing’ standard, originating in British law, generally includes more explicitly enumerated exceptions but with similar intent. Notably disputes over what constitutes fair-use are not easily administrable and can require protracted court proceedings to settle definitively.

For anyone wishing to circulate their work and grant others the right to re-use, remix, or re-distribute that work free of charge, coming to individual licensing arrangements with everyone who might want to do this is obviously impractical. To address this, there exist numerous pre-made ‘off-the-self’ licenses that you can apply to your work. Which of these you choose shapes how and under what circumstances others are permitted to re-use your work without infringing on your copyright.

Pre-made licenses exist that are tailored to the differences between different types of works. For example, there are licenses intended to be used for software and licenses intended to be used for other creative works such as images, prose (text), as well as hardware & designs.

In addition, there are now licenses tailored for machine learning or artificial intelligence models as these are comprised of several parts, including: training data, code, and model weights. Each of these parts may be licensed differently, and there is even some dispute as to whether model weights are subject to copyright at all under current law.

This is an area which is likely to see (by legal standards) rapid changes in the near future, given recent developments in the commercialisation of AI/ML models.

There are some general principles which apply to licenses across the different types of entity that they try to license. Licenses can generally be placed on a spectrum from proprietary, through permissive, to ‘share alike’ or ‘copyleft’ (the opposite of copyright). This spectrum is something of an oversimplification, and there are some extensions and caveats we’ll get to later.

What is ‘Free/Libre’ or ‘Open Source’ software?#

These same concepts developed originally in the context of software have often been applied to other creative outputs. Consequently, they are among the most developed and useful context for understanding the licensing of other things.

Software that is not free (in the ‘libre’ sense defined below) is proprietary. Software that you are not allowed to copy or modify falls into this category, as does software with usage restrictions, for example, “For research use only” or “For non-commercial use only”.

Permissively licensed things can generally be used by anyone for any purpose. A popular minimal example of this for software is known as the MIT license, for other works, CC0 the ‘public domain’ license. Copyleft licenses attempt to ensure that any re-distributions or derived works also remain ‘free’, the canonical example is the GPL. Unlike permissively licensed content, which can be modified and redistributed under a different license (including as a part of a closed and/or for profit project), copyleft content (modified or unmodified) must be distributed under the same, or a compatible license, which retains the copyleft obligation. In other words if you take copyleft content, modify it, and distribute your modifications, those modifications must also be copyleft.

The concept of copyleft licenses and their first example, the GPL, originated with Richard Stallman, who founded the free-software foundation (FSF) in 1985. The idea is a ‘hack’ of copyright law to use the protections that it affords to privately owned software to a software commons.

The FSF’s four fundamental freedoms of free/libre software are:

Freedom 0: The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose.

Freedom 1: The freedom to study how the program works, and change it, so it does your computing as you wish. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

Freedom 2: The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help others in your community.

Freedom 3: The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others. By doing this, you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

Other influential definitions of free and open source software include: The Debian project’s Debian Free Software Guidelines (DFSG), and the open source initiative (OSI)’s Open Source Definition. The terms ‘Free’/’Libre’ & ‘Open Source’ software are often used somewhat interchangeably, but have different connotations. The use of ‘free software’ typically denotes a more hardline political commitment to the ideals of the free software movement, and is associated with a preference for copyleft licenses. The name ‘open source’ places the emphasis on freedom 1 and could more readily be confused with the concept of ‘source available’ software, based on a naive interpretation of the name. ‘Open source’ is associated with, if not a preference for, then a more favourable view of, permissive licenses.

Note

The word ‘free’ in english does not distinguish something being monetarily free ‘gratis’ from politically free ‘libre’. This is often summarised along the lines of: “free as in speech, not necessarily free as in beer” Thus the phrase ‘libre software’ is sometimes encountered in English to succinctly distinguish the concept of software which respects your liberty from software which is finacially free to use (‘gratis’). This ambiguity confusingly leads to the name ‘Freeware’ which is software that can be copied without paying anyone, but comes without source and cannot be modified. The ‘free’ in ‘freeware’ is gratis but not libre. It is also common to encounter the acronyms FOSS (Free and open source software) and FLOSS (Free/libre and open source software)

The FSF contends that all software should respect these freedoms and that all software which does not respect these freedoms creates an asymmetric relationship between the users and developers of that software which can readily be abused by the developers to exploit their users. If developers are bad stewards of a free software projects, the friction for replacing them is lower, as all of the work put into the software does not need to be re-done. A ‘fork’ of the project can be made, developed and maintained by different developers whom the community of users deem a better steward. This is not true of proprietary projects where the developers own the rights to the code and thus cannot be readily replaced by the community of users if they begin to abuse these users who are now held captive by switching costs. It should be noted that an acrimonious project fork is quite uncommon and by no means always successful, it is the move of last resort. The credible threat of a fork redresses the power balance between developers and users giving users leverage if developers make unpopular choices.

Copyleft licenses are an attempt to ensure that software remains effectively under community ownership and cannot be used to make proprietary software which does not respect the four freedoms and may thus result in the abuse of its users. To attempt to achieve this goal, copyleft software requires that when distributing copyleft software or in some cases derived works that you do so under the same terms as the original license. Creative commons ‘share-alike’ licenses attempt the same thing for other content. One of the advantages of this approach is that the simplest way to redistribute your changes is often to contribute them to the ‘upstream project’ or to ‘upstream’ them. If you add some features to a codebase for your own use and contribute them upstream then you get the advantage of the assistance of upstream maintainers in keeping your code up to date and working correctly with the rest of the project. You don’t have to maintain your own fork and keep it up to date with the latest patches from the rest of the codebase and you don’t have to manage your own distribution. All this also means that everyone else benefits from your improvements and you benefit from everyone elses’. Being a good open source citizen means playing by these rules and, if you can, contributing your fixes and improvements to upstream projects; not just freeloading off of them.

Copyleft licenses do not prohibit commercial use, indeed numerous companies exist which develop copyleft projects. Many of those generate revenue through support services instead of selling licenses, which would incentivise an unhealthy relationship with their users. Nextcloud is an excellent example of a commercial, open source project. Nextcloud makes use of the AGPL v3.0 a license which extends the protections of the GPL to software used over a network. It gives users who interact with this software over a network, for example by using a web service, rather than run it on their own computers, the right to access a copy of the source code; which they are further free to modify and distribute as is usual for the GPL.

Within copyleft licenses, there are ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ copyleft licenses. ‘Strong’ copyleft licenses require that combined works which contain them as a library also carry the same license but weak copyleft licenses permit their re-distribution as a library within a combined work under a different license. We will define derived and combined works in the section on license compatibility where the detailed implications of the distinctions between strong & weak copyleft, and permissive licencing are explored in more practical detail. It is important to note that licenses can be incompatible such that creating a combined work is highly impractical to do legally.

| Free | Proprietary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Copyleft | Permissive | ||

| Strong | Weak | ||

| GPL1 CDDL2 | LGPL3 MPL4 | BSD5 MIT6 Apache | Research Only: No copying, No modification |

What are ‘Usage Restricting’ Licenses?#

Usage restricting licenses seek to affirmatively protect users or others affected by the use of the work by placing specific restrictions on its use. This curtails freedom 0, the freedom to use software ‘for any purpose’ and prohibiting the use of the software, or other system, for unethical purposes. Both ‘Ethical source’ & ‘Responsible AI’ Licenses are examples of this approach and seek to place restrictions on the uses to which the licensees can put the software or machine learning systems licensed in this fashion. Consequently, these licenses by the classical definitions of free and open source software from the FSF and OSI would not be considered free or open source licenses. They do however generally resemble them in the other three criteria of the definition. Their merits versus conventional open source licenses have been the subject of some debate, and their adoption has thus far been relatively limited.

Even an attribution requirement (the BY in CC-BY) can in some cases be considered a usage restriction. For example the Debian project found the Common Public Attribution License (CPAL) to be incompatible their free-software guidelines for this reason whilst it is approved by the Open Source Initiative. In the case of academic works attribution requirements can serve to re-enforce the citation convention with the force of copyright law.

Where to find open licenses for different types of work#

Code

The Open Source Initiaitive (OSI) maintains a list of approved licenses open source licenses

Free Software Foundation maintains a list of GPL-Compatible Free Software Licenses

choosealicense.com provides a tool to guide you through the license choice project.

Organisation for ethical source maintains a list of ethical source licenses

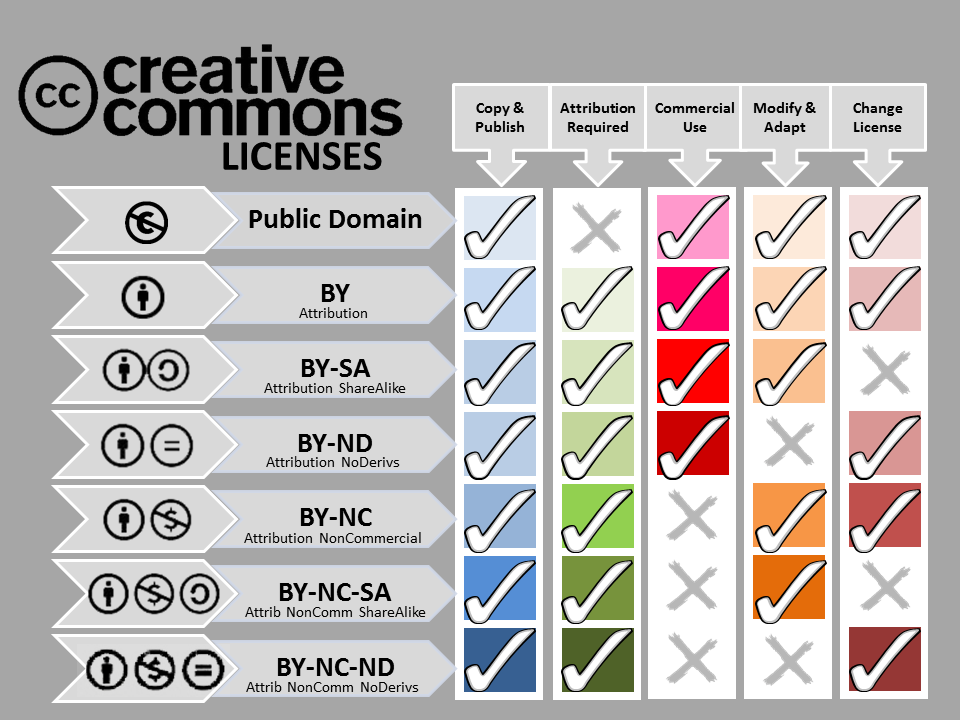

Prose, Images, Audio, Video, Datasets, and similar

-

Creative Commons License Chooser

Fig. 35 Creative Commons License Types. From George Washington University Libraries Open Textbooks. Used under a CC-BY 4.0 licence.#

-

Machine Learning (ML) / artificial intelligence (AI) systems

Creative commons and Software licenses can be applied to different parts of ML/AI systems, CC to training data and weights, software licenses to code used in training / deployment.

Licencing enforcement#

There have been a number of successful legal cases that have been brought in defence of the terms of copyleft licenses obliging the parties abusing the terms of these licenses to appropriately release their code. But this can be hard to discover, as it is not immediately obvious if copyleft code has been used from looking at a black box proprietary end product.

Organisations which take legal action in defence of free software, and which can provide information and resources for anyone else seeking to do the same, include:

Pertinent edge cases#

Contributor license Agreements#

The holder of the copyright on a copyleft project can still re-license that project or dual-license that project under a different license, for example to grant exclusive rights to commercially distribute that project with proprietary extensions or to make future versions proprietary. In a large community developed project, this would require the consent of all contributors, as they each own the copyright to their contributions. To get around this, some copyleft projects developed by companies that commercially license proprietary extensions to these projects ask their contributors to sign contributor license agreements (CLAs) which may assign the contributor’s copyright to the company, or include other provisions so that they can legally dual-license the project.

Being a welcoming space to those who do not want to use proprietary software#

Some people avoid using non-free software on principle to the greatest extent that they can. It is highly impractical to completely avoid all non-free software in the world today, so many have compromises and workarounds. This might include measures such as only running proprietary code in a sandboxed environment like a web browser, but this can impose an additional burden on these users. This is especially true if proprietary tools do not offer first class features in browsers or support free software operating systems like Linux. Consequently, the choice to use open infrastructure is important if you want to be inclusive of people who adhere strongly to the free software ethos and consider being asked to use non-free software as an imposition. A small minority of people simply will not participate if doing so requires that they use non-free software.

How and where to add licenses#

Wherever you share your project it is likely to be organised in a hierarchy of directories, place a plain text file containing the license in the top level directory of your project.

If it is a git project for example that is shared on a git forge like GitHub or GitLab, using a standard file name like LICENSE will allow your license to be picked up the host and displayed on your project.

If the license that you have used has a standardised short name from SPDX then this will be displayed as a small icon on your projects home page by these hosts.

It can also be useful to include license information in the form of standard strings at the top of each text file in your project.

There are useful tools which automate this available from REUSE a project from the FSFe which developed the spec.

This is especially true if your project contains material that is licensed in multiple different ways or a part of your project is being used in someone else’s which uses a different (compatible) license.